How to Tell a Story with Just One Photo: The Secret Behind Visual Hooks

The Buzz Around Visual Storytelling

For the past few years, it has been quite trendy to throw around the term visual storytelling. Recently, I read a blog post about how to incorporate story into your images. I agree—this is very important. Not just for the blogger or journalist, but for any photo. At its core, every photo is telling a story.

But sometimes I feel instructors make it harder than it needs to be. Not intentionally—there’s no devious plot unfolding. I think we just get carried away with the details and lose sight of the basics.

In fact, just last week I explored this idea using a rickshaw photo I took in Kolkata. That image sparked a whole conversation around curiosity and visual tension—and it reminded me how much story can live in a single frame. If you missed that post, you can read it here.

Simple Stories Stick

Often, though not always, the best stories—or shall we say, the most lasting ones—are the simplest. We all remember the stories we were told as children: Little Red Riding Hood, Goldilocks, Cinderella. These are all simple, sticky stories. By “sticky,” I mean they’ve lasted lifetimes, told over and over from generation to generation. Credit for this term goes to the Heath Brothers in their brilliant book Made to Stick.

I once asked master photo essay guru Brian Storm what the essential parts of a photo essay are. He looked at me like I was an idiot and said simply: “The beginning, the middle, and the end.”

I felt stupid. I had wanted something complicated and profound. But his answer was profound—because simplicity often is.

Let’s take Cinderella as an example:

-

- Beginning: Cinderella loses her family and is raised by an evil stepmother.

- Middle: She gets a fairy godmother, goes to the ball, and meets the prince.

- End: The prince finds her and they live happily ever after.

Can a Single Photo Tell a Full Story?

So, can this idea of beginning, middle, and end translate to a single photograph? I believe it can—but to do so, we need to simplify even further. We’re not talking content here, but movement and time.

When someone looks at your photo, you have milliseconds to grab their attention and keep it. This is the “grab” at the start of a story—the first line or paragraph that pulls you in. Consider these great literary hooks:

“The great fish moved silently through the night water, propelled by short sweeps of its crescent tail.” —Peter Benchley, Jaws

“It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen.” —George Orwell, 1984

“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” —Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice

“There was a boy called Eustace Clarence Scrubb, and he almost deserved it.” —C. S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

These hooks compel you to keep reading. A photograph is different, of course—but also not. A strong image has to grab and hold attention just as effectively.

The Beginning: What Grabs a Viewer’s Attention?

So what grabs someone’s attention in a photo? There are many tools:

-

- Composition

- Emotion

- Light subject over dark

- The human form

Let’s focus on the strongest of these: the human form.

Research has shown that a viewer’s attention is grabbed and held within a photo by the human face. In 2015, The Poynter Institute, and a team of researchers led by Sara Quinn Media asked the question, “What makes a photo worth publishing?” The study was funded by the National Press Photographers Association (NPPA). Quinn found that “people look first at faces. And they are interested in the relationships between people in the frame, often looking back and forth, between faces and interactions.”

We don’t know exactly why—some suggest it’s a human connection, a sense of identification. Whatever the reason, we need to be aware of it and use it.

But What If There’s No Human Form?

Then it becomes even more critical to understand the other elements: composition, visual space, color, lines. These tools become essential to attract attention. But once you’ve grabbed attention, then what?

Here I used composition, color, and context to grab viewers right away.

The Middle: The Movement or Moment

Once you have a viewer’s attention, you have to keep it. In writing, this is the “middle”—the plot development that pulls you through. In photography, this is movement—or better yet, the moment.

Henri Cartier-Bresson called it the “decisive moment”—that instant in time when everything comes together. The kiss just before lips meet. The punch just after the fist leaves the face. These moments create tension, and tension is the fuel of visual storytelling.

Tension makes us wonder: What’s happening next? What just happened? That emotional or narrative pull keeps the viewer engaged.

The NPPA study called this a genuine moment—an image that connects deeply with the viewer. A decisive moment is a peak in time; a genuine moment is a peak in emotion. Both create curiosity and draw us in.

Golman and Loewenstein, in their paper Curiosity, Information Gaps, and the Utility of Knowledge, write: “There is a natural inclination to resolve information gaps, even for questions of no importance and even when all possible answers have neutral valence.” In short, curiosity happens when we sense a gap in our knowledge. And that’s incredibly useful in photography.

If a photo is too obvious or staged, we lose interest. But when the moment is decisive or genuine, we want to know more.

Both the decisive moment and the genuine moment can act as the initial grab. I can’t overemphasize how powerful this is—not just for drawing the eye, but for planting the seed of a story in the viewer’s mind.

What About the End?

We’ve talked about the beginning and the middle—but what about the end?

In traditional stories, the end brings resolution. In photography, that can be trickier. A single image doesn’t have the luxury of time, but it can still deliver a feeling of closure or completion.

Sometimes the “end” in a photo is subtle: a visual payoff, a symbolic gesture, or a mood that feels final. Other times, it’s unknown—like a cliffhanger. That’s okay too. Not every photo needs to wrap up cleanly. Some of the best ones leave us with questions.

A strong ending in a photo might:

-

- Show what happens next or imply it

- Create a visual loop that brings the eye back around

- Provide emotional resolution or context

It’s less about tying things up neatly and more about giving the viewer enough to feel satisfied—or intriguingly unsettled.

Example: The Rickshaw Story

I was doing a story on the rickshaw pullers of Kolkata—the last of a dying breed. These are the only remaining foot-pulled rickshaws in the world, and they’re fading fast.

My first attempt was to show an empty rickshaw, maybe with a taxi going by—to imply the taxi is working, while the rickshaw is not

It was missing something crucial: the human element.

Then the rickshaw puller returned and entered my frame. Good timing.

Still, something was missing.

I waited, took many more photos, knowing I wanted layers: taxis, cycles, auto rickshaws—all moving in contrast to the stillness of the hand-pulled rickshaw.

What I ended up with was this image:

With this image, there’s something close to a complete story. The viewer is grabbed by the human form and pulled through the image by the decisive moment: a yellow taxi, a bicycle, and a cycle rickshaw all pass while the hand-pulled rickshaw waits for business.

What’s the “end” here? Admitidly, it’s subtle. The rickshaw puller has returned, but he’s not moving. The world speeds past him—taxis, bicycles, progress. The contrast resolves the story: the old world waits while the new moves on. That quiet tension is the ending.

I like this example because it shows that a decisive moment isn’t always serendipitous. Sometimes you have to work for it.

Want your photos to tell deeper stories? Start with a hook. Show us a moment. Leave us curious.

And remember, visual storytelling isn’t just about taking good photos or telling random stories. It’s about using your images to communicate purpose, evoke emotion, and prompt people to action. Whether you’re working for an NGO, documenting culture, or trying to inspire change—your stories have the power to move people. So give them something worth remembering.

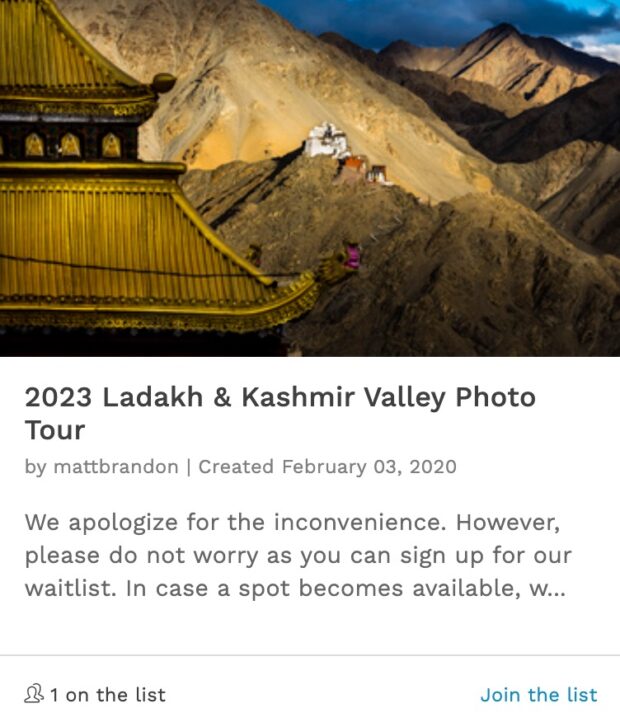

If you’re inspired by the power of storytelling through photography and eager to sharpen your skills, join us this September 12–20, 2025, for an immersive workshop in Sumatra, Indonesia. We’ll explore the dynamic Pacu Jawi tradition and the rich culture of the Mentawai people. It’s a rare chance to capture compelling narratives and grow your craft in extraordinary settings. Only one spot remains—secure your place today and be part of this unforgettable journey.